Working papers are intended to make results of my ongoing research available to others and to encourage further discussion on the topic. Comments and clarification are welcome. This paper discusses Milpar’s history, its bayonet production, and collecting community concerns regarding Milpar bayonets.

Columbus Milpar & Manufacturing Co. (Milpar) arose as the defense contracting division of a Columbus, Ohio, commercial metal stamping firm. Vietnam Era defense contracting overshadowed the commercial business, becoming the company’s identity as we know it. A series of leadership changes drained away top-level manufacturing knowledge, leaving revenue growth as firm’s overarching goal. This led to acquisition, but had introduced serious problems that contributed to Milpar’s demise.

The study of Milpar’s bayonet production enables us to follow Milpar’s rise and fall in real-time. This research also builds on Gary Cunningham’s work, fleshing out additional particulars of Milpar’s contracts. While there remains a need for further research, especially with respect to M7 bayonets, new findings bring Milpar’s bayonet production into sharper focus.

Company History

The Columbus Stamping Co. was founded in 1946.[1] By 1949, it was known as the Columbus Stamping and Manufacturing Co. [2] Company founders were all highly-skilled metalworkers, with extensive industry experience: President Frank M. Rodgers had previously worked at the Columbus Bolt Works.[3] Columbus’ oldest and largest forge, Columbus Bolt Works (aka Columbus Bolt & Forging) became the Stamping Co’s largest customer.[4] Vice-President Delbert P. Palmer and Treasurer Henry W. Markiewicz were both tool and die makers, who had formed Dalmar Tool and Engineering in Chicago, which they closed in 1945 to enter into partnership with Rodgers.[5]

In January 1954, Rodgers and Palmer also incorporated The Midwest Oil and Gas Company. Rodgers was president and Palmer, vice president. The treasurer was a young Ohio attorney, Eugene C. Fresch. [6] A World War II veteran, after graduating from law school in 1952, [7] he briefly worked as an attorney for the State Division of Securities[8] before joining Midwest Oil & Gas.[9]

In November 1954, an aircraft piloted by Columbus Stamping Treasurer Henry Markiewicz; also carrying his wife and two children, crashed returning home from a Thanksgiving visit to Wisconsin. All aboard perished.[10] Fresch then became Secretary/Treasurer of Columbus Stamping.[11]

In 1955, Columbus Stamping moved its plant to 3450 E. Fulton Ave., which would remain the Ohio headquarters until operations ceased in 1970.[12] The earliest references to “Milpar” date from 1959.[13] Milpar did not replace Columbus Stamping. Columbus Stamping help-wanted advertisements were found as late as November 1966. [14] Milpar may simply have been created for recordkeeping purposes, to separate government contracting from commercial business.

In 1959, Milpar hired Jerome “Jerry” Nakrin as vice president of sales and purchasing. Nakrin came to Milpar from Standard Products Co. [15] Standard Products is best known to bayonet collectors for having manufactured latch plates used on Second World War M4 bayonets.

Nakrin became Milpar vice president following the August 1960 death of Frank Rogers.[16] About that time, Delbert Palmer founded a Columbus plastics firm, Allied Custom Molded Products,[17] [18] and appears to have exited Milpar in the early-1960s. By 1965, Nakrin was Milpar president.[19] The exact timing of Palmer’s exit and Nakrin’s becoming president are not known.

In November 1964, Louis J. Michles joined the company. A First World War combat veteran, he had extensive metals industry experience, having founded/operated a number of businesses in Ohio, including: steel & scrap iron, industrial/govt. surplus, and trucking firms. [20]

In early 1966, two events occurred that fundamentally changed Milpar’s trajectory: on February 23rd, Louis Michles suffered a fatal heart attack in his Milpar office.[21] By March 10, Nakrin had, apparently, departed Milpar and Eugene Fresch became the fourth Milpar president since 1960.[22] The circumstances of Nakrin’s departure are not known.

Milpar’s loss of top-level technical and manufacturing knowledge from 1960–66 was profound. Unlike Rodgers, Palmer, Nakrin, and Michles; Fresch’s industry knowledge was derived from his role as an attorney and treasurer. This was manifest in his vision for the company, stated in 1967: “to diversify its business on top of the backlog of bayonet orders it now has.”[23] This resulted in a massive contracting expansion (reaching $26–27 million per year 1967–69).[24] This exacerbated already serious company-wide operational issues.

In 1967, with sales upwards of $20 million[25] and assets valued at $10.8 million,[26] Fresch began shopping Milpar for acquisition. In February 1968, Milpar was purchased by Whittaker Corp., a publicly-traded Los Angeles conglomerate, becoming Whittaker’s Columbus Milpar Division. Fresch and others with an ownership stake received Whittaker Corp. common stock.[27] Fresch and two other Milpar executives were retained on a five-year commitment.[28]

Ownership by a publicly-traded corporation brought a new level of scrutiny to Milpar’s operations. Fresch and his managers soon found themselves in hot water. As detailed below, two weeks after the acquisition was finalized, federal inspectors shut down bayonet production completely at the New Lexington plant for over a month due to quality issues. In October 1968, Fresch was quoted in the press, indiscreetly speaking, still, of overwhelming problems at the New Lexington plant.[29]

In 1969, the failed implementation of a $3.2 million automated production line for producing cluster bomblets cost another $3 million to put right. In a misguided response to the financial impact, Milpar managers lowered quality control standards to increase profitability. A Whittaker Corp. “rescue team” sent in to salvage the situation discovered a build-up of inventories that further eroded Milpar’s financial performance.[30]

In fall 1969, Whittaker Corp. parted ways with Fresch[31] and filed a $75 million lawsuit against three former Milpar executives for “failing to devote time & energy; and misrepresentations/ failure to disclose problems prior to the sale.”[32] In their 1969 year-end press release, Whittaker Corp. announced that they would discontinue Milpar operations.[33] Whittaker simply allowed Milpar operations to wind-down, ceasing in mid-1970 as existing defense contracts were completed. Whittaker Corp. then replaced President and CEO, William Duke, who became the final casualty of Milpar’s demise.[34]

Milpar Operations

My survey found $101.6 million in defense prime contracts awarded to Milpar 1961–69. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) digital archives cover contracts awarded 7/1/1965–6/30/1975. The earlier period was compiled from a variety of sources, including private and govt. publications; and newspaper reports. Bayonets appear to account for just under $4 million or 3.9 percent. Table 1 summarizes ordnance items produced by Milpar:

| Table 1: Defense Items Produced by Milpar 1961–1970 | ||

| Description | Federal Supply Class (FSC) | Class Description |

| M5A1 Bayonet | 1005 | Guns, through 30 mm |

| M6 Bayonet | ||

| M7 Bayonet | ||

| 81 mm. Mortar Projectile Fuse | 1315 | Ammunition, 75 mm through 125 mm |

| 105mm Target Practice Tracer M490 Cartridge | ||

| Metal Parts for Cluster Bomblets BLU-24/B and BLU-66/B | 1325 | Bombs |

| MK 14 and Mk 15 Bomb Fins (for 250 & 500 lb. Snakeye Low-Drag Bombs) | ||

| Arming Wire Assemblies for Bomb Fins | ||

| Nozzle and Fin Assemblies for 2.75-in. Rocket | 1340 | Rockets, Rocket Ammunition and Rocket Components |

| Nozzle and Fin Assemblies for 5-in. Zuni Rocket | ||

| Metal Parts for M16A1 Anti-Personnel Mine (Bouncing Betty) * | 1345 | Land Mines |

| Flight Helmet Oxygen Mask Receiver | 1660 | Aircraft Air Conditioning, Heating, and Pressurizing Equipment |

| Jet Pilot Survival Knife * | 7340 | Cutlery and Flatware |

| Mess Kit* | 7350 | Tableware |

| * These contracts appear to have only been awarded 1962–1964, so do not appear in the NARA Database. | ||

With one exception, all of Milpar’s FSC 1005 contracts were Weapons Program contracts, which are consistent with bayonet procurement. It also bears noting that the Jet Pilot Survival Knife is not a weapon under FSC 1005, but is a “hunting knife” under FSC 7340.[35]

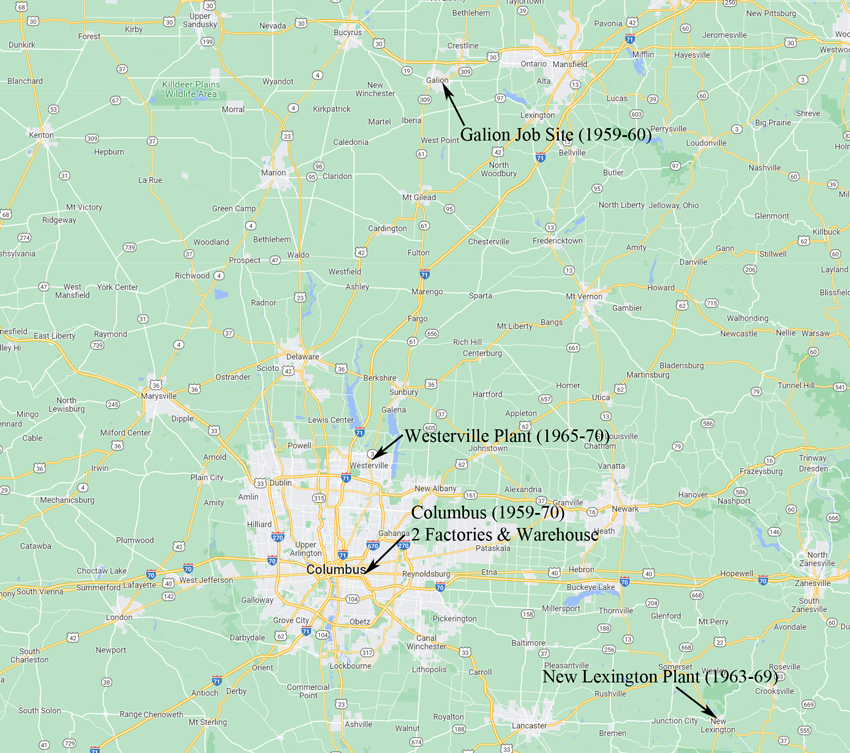

At its zenith in 1968, Milpar employed around 1,150 at five facilities. Figure 1 shows the sites where Milpar operated 1959–1970.

Figure 1: Map showing the locations where Milpar operated.

Milpar began factory operations at the existing Fulton Ave. Columbus Stamping plant. At some point Milpar opened two additional Columbus facilities: one on E. 5th Ave. and another on Cassady Ave.[36] At their peak, the Columbus facilities (2 plants and a warehouse) employed about 350.[37]

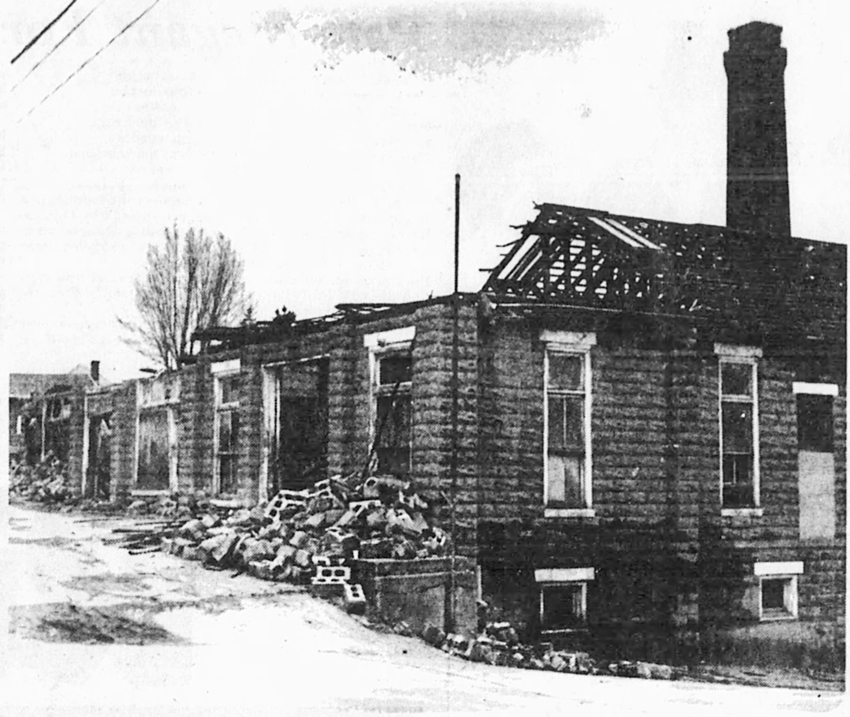

In 1963, Milpar opened a plant in New Lexington, about 50 miles southeast of Columbus, that would become the focus of bayonet production. [38] Milpar leased the former Evans Reamer & Machine Co. Building No. 2, a vacant ca. 1916 Buick garage turned into a factory building[39] that had been gifted to the Village ca. 1960.[40]

Milpar’s smallest plant, its limitations proved problematic when Milpar began to manufacture bayonet parts there. Employment would peak at close to 100, but only briefly. For most of its existence, “full staffing” was about 60.[41]

Figure 2: Taken in 1985, the only image found of the New Lexington plant building where Milpar produced bayonets from 1963–69. The building was demolished in 1986. Today, the original concrete slab serves as a parking lot. (Times Recorder, Zanesville, OH, used with permission)

Due to New Lexington’s high unemployment, local firms received federal contracting preferences (set-asides) not available in Columbus. [42] This probably explains why Milpar went there, as they clearly attempted to leverage New Lexington to obtain set-asides. In 1965, they sought the set-aside portion of a large bomb fin contract, citing intent to make fins at New Lexington. The Dept. of Defense (DOD) nixed the set-aside, because the plant so clearly lacked capacity for such a big job. DOD further expressed its displeasure with Milpar by naming them in a story published in their industry newsletter, putting others on notice not to pull this stunt.[43]

In 1965, Milpar opened a plant in Westerville, on the northern edge of metropolitan Columbus, about 15 miles from Milpar’s Columbus headquarters.[44] The buildings used by Milpar were built in 1942 and much of it remains in use today. The Westerville plant primarily produced 81 mm. mortar round fuses and components for aerial bombs. Milpar’s largest plant, at its peak Westerville reportedly had 700 employees.[45]

From 1946–58, Columbus Stamping made little news, save for the tragedy that claimed the Markiewicz family. However, from its inception, Milpar’s operations regularly made news.

What appears to be Milpar’s first government contracting job ran from late-1959 to mid-1960.[46] Evidence is lacking regarding exactly what the job entailed. Milpar performed the work on-site at the New York Central Railroad Yard in Galion, OH, about 60 miles north of Columbus.[47]

On October 29, 1959, the Galion Fire Dept. responded to the railroad yard when sparks ignited “a huge stockpile of rubber Army treads belonging to the Columbus Milpar Manufacturing Co.”[48] Between January–May 1960, no fewer than 20 different employees were treated in the emergency room at Galion Community Hospital for injuries sustained while working at the Milpar site. The last accident/injury report found was May 18, 1960, so the job likely concluded shortly after.[49]

On January 25, 1962, the Columbus plant was ordered closed by inspectors for safety violations after a mass casualty incident where 106 employees were overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning. 50 were treated and released at the scene; 56 were transported to hospitals, 19 of whom had to be admitted.[50]

The initial two-year New Lexington building lease was for $1 per year, plus payment of taxes and insurance.[51] When the lease ran out in March 1965, Milpar delayed seven months until verbally notified of a large new bayonet contract to conclude lease negotiations. This enraged one village councilman, who opposed renewing the lease and angrily spoke out in a public meeting about Milpar stalling until notified of a new contract before agreeing to pay the village rent.[52]

When manufacture of bayonet parts began at New Lexington in 1966, homeowners and businesses started complaining of yellow fallout from the plant’s smokestack that damaged paint on homes/buildings. In September 1967, two long-complaining residents filed claims against the village for reimbursement of painting costs. The village government was in a bind: if they paid the claims, more residents and businesses near the plant would file; however, they could ask, but could not compel Milpar to accept liability and settle the claims.[53] The claims sat with Milpar’s attorney until the firm’s 1968 sale to Whittaker Corp., after which they were forwarded to languish in Whittaker’s Los Angeles corporate legal department.

In spring 1969, a group of 79 Columbus residents filed a $500,000 lawsuit over “incessant noise caused by the company’s operations.” In July 1969, an overheated tank containing a salt solution exploded, blowing out a five-foot section of the Columbus plant wall.[54]

In August 1969, the theft of 1,000 detonators from the Westerville plant’s explosives magazine was believed by the FBI to have been perpetrated by two children.[55]

In December 1969 and January 1970, 43,000 pounds of rolled aluminum was stolen from the Columbus plant. Four employees were arrested for the theft, as was a local junk yard owner who purchased the metal, then attempted to conceal it from authorities.[56]

Operations at the New Lexington plant ended by March 1969 as the backlog of bayonet orders was completed. However, Whittaker Corp. maintained the building lease for an extended period. The Columbus plant(s) began a three-month phased closure on January 31, 1970, after which remaining work and staff were transferred to Westerville.[57]

In February 1970, Whittaker Corp. noticed New Lexington that they would begin vacating the plant there. Although the plant was “closed,” Whittaker Corp. put a small crew to assembling bayonets as they prepared to dispose of the machinery and inventory stored there.[58] Five to eight employees were reported as still assembling bayonets as of April, 30 1970. By then, only 50 employees remained at Westerville, [59] which closed soon after, ending Milpar’s operations.

Bayonet Contracts

Bayonets were a significant part of Milpar’s early government contracting, until other ordnance items became dominant. What appears to be the last bayonet contract was awarded in June 1967. Table 2 summarizes what appear to be Milpar’s bayonet-related contracts.

| Table 2: Milpar Bayonet-Related Contracts | |||||

| Bayonets Ordered by Army Weapons Command, Rock Island Arsenal, IL |

|||||

| Contract # | Date | FY | Amount | Type | Notes |

| DA-11-199-ORD-601 | Feb-61 | 61 | $706,296 | M6 Bayonet | Contract details per GAO protest decision. |

| Mar-61 | 61 | $127,240 | |||

| DA-11-199-AMC-??? | Apr-62 | 62 | $369,508 | M5A1 Bayonet | |

| DA-11-199-AMC-270 | ? | 64 | $365,458 | M6 Bayonet | Amount per SBA report. |

| DA-11-199-AMC-625 | May-64 | 64 | $186,996 | M7 Bayonet | Amount estimated. |

| DA-11-199-AMC-642 | Aug-65 | 66 | $66,000 | Not Stated | Foreign Military Sales. Likely M5A1 bayonet. |

| DA-11-199-AMC-659 | Jan-66 | 66 | $165,000 | M6 Bayonet | M6 Bayonets per package label dated 3/67. |

| Jun-66 | 66 | $165,000 | |||

| DA-11-199-AMC-670 | Feb-66 | 66 | $277,000 | Not Stated | Probably M7 bayonet |

| Apr-66 | 66 | $277,000 | |||

| DA-11-199-AMC-667 | Apr-66 | 66 | $455,000 | Not Stated | Probably M7 bayonet. |

| DA-11-199-AMC-726 | Jun-66 | 66 | $561,000 | M5A1 Bayonet | M5A1 Bayonets per package label dated 10/68. |

| DAAF03-67-C-0068 | Jun-67 | 67 | $103,000 | Not Stated | Probably M7 bayonet. |

| Ordered by Marine Corps Supply Activity, Philadelphia, PA (Direct procurement by USMC) | |||||

| M00150-67-C-0176 | Oct-66 | 67 | $37,000 | Not Stated | Probably M7 bayonet. |

| Armory/Depot Repair Parts | |||||

| Contract # | Date | FY | Amount | Notes | |

| DA-19-058-AMC-1267 | Oct-65 | 66 | $38,000 | Ordered by Springfield Armory | |

| DA-19-058-AMC-1283 | Oct-65 | 66 | $11,000 | Ordered by Springfield Armory | |

| DAAF03-66-C-1006 | Feb-66 | 66 | $15,000 | Ordered by New York Army Procurement Detachment | |

| DAAG11-66-C-0771 | Oct-66 | 67 | $16,000 | Ordered by Chicago Army Procurement Detachment | |

| DAAG25-67-C-1386 | Dec-66 | 67 | $25,000 | Ordered by New York Army Procurement Detachment | |

| DAAG31-67-C-0799 | Dec-66 | 67 | $21,000 | Ordered by Cincinnati Army Procurement Detachment | |

Milpar’s first bayonet contract, DA-11-199-ORD-601, was awarded February 15, 1961, for 342,000 M6 bayonets, plus final inspection gauges. Two weeks later the government exercised an option for an additional 65,000 bayonets. An initial quantity of 4,900 bayonets was due July 15, after which monthly deliveries of 31,000 bayonets were expected until completion in September 1962. However, by January 1962, only 32,500 of 160,000 expected bayonets had been delivered.

In December 1961, Milpar bid on another contract for 190,000 M5A1 bayonets, plus repair parts. The contracting board recommended rejecting Milpar’s bid due to the M6 backlog, and out of concern that Milpar lacked production capacity to produce expected quantities of M6 and M5A1 bayonets concurrently. Camillus Cutlery Company protested the proposed contract award to the General Accounting Office (GAO), citing Milpar’s late deliveries.

Matters involving a small business bidder’s capacity require a determination by the Small Business Administration (SBA). The SBA issued a Certificate of Competency (Certification) finding that Milpar had adequate capacity. In April 1962, the GAO ruled that the Certification was controlling and ordered the M5A1 contract be awarded to Milpar.[60]

According to Gary Cunningham, Milpar delivered 182,804 M6 bayonets during fiscal year 1964 (7/1/63 to 6/30/64) under contract DA-11-199-AMC-270.[61] I found evidence of a contract awarded to Milpar during that same time in the amount $365,457.57.[62] This amount is spot-on for the quantity of M6 bayonets Cunningham reported delivered.

Also, according to Cunningham, Milpar was awarded contract DA-11-199-AMC-625 for M7 bayonets on May 7, 1964. This was the first government M7 bayonet contract. 93,498 M7 bayonets were reported delivered under this contract.[63] Milpar was slow to begin production, with initial production samples not submitted to the government until February 1965.[64]

In August 1965, Milpar was awarded a $66,000 FSC 1005 Weapons Program contract that was placed for foreign military sales. Contract DA-11-199-AMC-642 is the only bayonet contract found for any maker 1965–1975 that is documented as placed for foreign military sales. [65] Circumstantial evidence suggests that this foreign sales contract was likely for M5A1 bayonets. In mid-1965, there was no demand for M6 or M7 bayonets for foreign military sales, as no M14 or M16 rifles had yet been provided to foreign users.

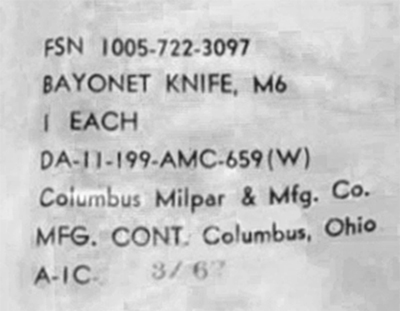

In November 1965, Milpar announced a new 350,000–400,000-unit bayonet order.[66] This is consistent with two contracts formally awarded to Milpar in January and February 1966. Contract DA-11-199-AMC-659 was for M6 bayonets (ref. Figure 3) in the amount $165,000 and DA-11-199-AMC-670 in the amount $277,000. Both contracts included options to double the order, which the government exercised in April 1966 and June 1966 respectively.

Figure 3: Image of package label validating that contract DA-11-199-AMC-659 was for M6 bayonets.

Two new contracts were also awarded to Milpar in April and June 1966. Contract DA-11-199-AMC-667 in the amount $455,000 and DA-11-199-AMC-726 for M5A1 bayonets (ref. Figure 4) in the amount $561,000.

In October 1966, Milpar was awarded a $37,000 Marine Corps direct contract; and, in June 1967, an Army contract in the amount $103,000 that appears to be the final Milpar bayonet contract. [67]

The majority of Milpar’s M7 bayonets were produced 1966–68, a time when every M16 Rifle and M7 bayonet manufactured went into service as fast as they could be obtained. As a result, observing Milpar M7 bayonets in original factory packaging has proven illusive. Now that we can identify Milpar’s M5A1 and M6 contracts; and by using the M7 bayonet quantities reported delivered 1966–67 from Gary Cunningham’s research for validation, the picture shown in Table 3 emerges.

| Table 3: Fiscal Year 1966 and 1967 Contracts That Analysis Suggests Were for M7 Bayonets | |||

| Contract # | Date | FY | Amount |

| DA-11-199-AMC-670 | Feb-66 | 66 | $277,000 |

| Apr-66 | 66 | $277,000 | |

| DA-11-199-AMC-667 | Apr-66 | 66 | $455,000 |

| M00150-67-C-0176 | Oct-66 | 67 | $37,000 |

| DAAF03-67-C-0068 | Jun-67 | 67 | $103,000 |

| Total | $1,149,000 | ||

| Estimated Quantity @ $2/bayonet | 574,500 | ||

| FY 1966 & 67 Quantity Reported by Gary Cunningham[68] | 563,530 | ||

Bayonet Production

Until 1963, Milpar manufactured, assembled, and packaged bayonets at the Columbus plant. Assembly and packing of bayonets began at New Lexington in April or May 1963.[69] Bayonet parts were still manufactured at the Columbus plant, then were shipped to New Lexington for assembly.

Initially, the New Lexington plant was devoted to both assembly of land mines (w/o explosives) and bayonets.[70] After completing the land mine contract in late-1965, the plant was devoted primarily (if not entirely) to bayonet production until its March 1969 closure.[71]

Bayonet parts manufacture increasingly had to compete with larger jobs for Columbus factory space. In March 1966, just days after the death of Louis Michles and departure of Jerome Nakrin, Milpar president Eugene Fresch announced that manufacture of bayonet parts would begin to shift from Columbus to New Lexington. He also indicated that Milpar had a backlog of bayonet production that would take the rest of the year to liquidate. [72]

By May 1966, what Fresch announced that “unforeseen … engineering delays in changing the [New Lexington] plant” had bayonet production at a standstill. Nearly all the employees were laid off. The stoppage impacted production of “three styles of bayonets.” On June 10, Milpar reported that they expected to resume production before July 1.[73]

This shows that, from early 1966, Milpar was producing M5A1, M6, and M7 bayonets concurrently. At this time, Milpar had a 9-month backlog. Between April-June 1966, when the plant was mostly shut down, new government orders added approximately 700,000 additional bayonets to the existing backlog.

In January 1967, Milpar reported that they were still working to liquidate backlogs, while producing two “lines” of bayonets.[74] (However, evidence supports they produced all three bayonet types at this time. Perhaps, M5A1 and M6 bayonets were being assembled on the same production ‘line’ and M7s on another.)

In August 1967, the backlog of bayonet orders was still expected to take 6–8 months to complete with 90 staff.[75] The reference to 90 staff was illusory (likely a device to make the backlog appear smaller than it really was). From mid-1966 through mid-1968, actual staffing appears not to have exceeded the 60s.[76]

On February 21, 1968, it was reported that production at the New Lexington plant had been stopped for the last several weeks after “the firm ran into trouble with government rejections.” In early February, practically all [employees] were laid off.[77] The shutdown continued well into March.[78] The backlog of bayonet orders was expected to take until mid-1968 to complete with 100–110 staff.[79] (Another illusory staffing level to downplay the increasing backlogs.)

In August 1968, Fresch reported that new work for the New Lexington plant was expected soon (there was a large M7 bayonet contract solicitation underway).[80]

In October 1968, staffing was reported as “close to 100 employees ...” (the peak staffing level at New Lexington). Fresch also reported that “we have so many problems there [New Lexington] that we don't know what's next. They’re technical problems with the government ...” (i.e., more quality control issues). Figure 4 illustrates just how backlogged production was at this point.

Figure 4: This M5A1 bayonet from the June 1966 contract was packaged in October 1968.

In October 1968, the government reached its breaking point with Milpar’s bayonet production problems. Despite Milpar being low-bidder, the Government awarded the new M7 bayonet contract to Bauer Ordnance Corp. of Warren, MI.[81] Fresch would later confirm this, indicating "We lost our product line to a competitor in Michigan ..."[82] Asked what caused loss of the contract, Fresch described the mid-1966 to fall-1968 period as “a little late on delivery and a little quality problem. We were low bidder, but they went to others.”[83]

By January 8, 1969, the plant was reported down to 27 employees.[84] By March, the plant was closed, having completed the backlog of bayonet orders.[85]

Using reported deliveries and estimating using dollar amounts for contracts where delivery quantities have not been reported, Milpar appears to have produced an estimated 1.9 million bayonets from 1961–69. An estimated breakdown by type is shown in Table 4.

| Table 4: Estimated Number of Bayonets Produced by Milpar 1961–1969 | |||

| Type | Quantities Reported | Unreported Quantities Estimated | Total |

| M5A1 | 190,000 | 295,111 | 485,111 |

| M6 | 589,804 | 157,894 | 747,698 |

| M7 | 657,028 | 657,028 | |

| Grand Total | 1,889,837 | ||

Collecting Community Concerns

Milpar’s bayonet production exhibits, by far, the greatest number of manufacturing variations of any post-War M4–M7 Series bayonet contractor. Lack of evidence regarding Milpar and its production has hindered an understanding of Milpar’s manufacturing variations, in some ways serving to magnify their significance, while falling short of providing an explanation. An understanding of Milpar and their troubled bayonet production helps explain why their bayonets exhibit so many quirky manufacturing variations.

Unexplained manufacturing variations combined with the knowledge that bayonets have been assembled by commercial dealers using rejected or surplus Milpar parts has created dissonance for collectors who want a sure way to know whether a bayonet they purchased (or want to purchase) is “government issue.” Discussion of known episodes involving commercial-assembly helps to illuminate the scope of commercial-assembly vs. government-contract production.

This dissonance has heightened concerns that many M4–M7 Series bayonets encountered today are commercially-assembled. However, evidence shows that the true extent of commercial assembly is fairly limited, especially when taken in the context of government-contract production.

This has also given rise to conjecture regarding bayonets distributed to foreign users; and, the presence or absence of the Defense Acceptance Stamp (DAS). However, evidence shows that these are myths; and, neither an explanation for manufacturing variations nor a cause for concern.

What I add here is additional context, recapping circumstances affecting Milpar’s government-contract production that help explain Milpar’s manufacturing variations; acknowledge valid concerns regarding commercially-assembled bayonets; and, bring perspective to those concerns.

Milpar Manufacturing Variations

The most significant manufacturing variations appear to be a function of the blade stamping processes used by Milpar. However, additional minor variations likely resulted from the circumstances detailed above. There were three distinct Milpar bayonet manufacturing evolutions:

1. 1961–1965, when bayonet parts were manufactured at the Columbus plant;

2. Spring 1966–Spring 1968 when bayonet parts manufacture was incompetently moved to New Lexington, becoming increasingly-problematic until the government shut down production in January or February 1968; and,

3. New Lexington plant manufacture under Whittaker Corp. oversight after the early-1968 shutdown.

It took nearly two months to get the production line running following the May 1966 relocation of bayonet parts manufacturing from Columbus to New Lexington. Even if the goal was to replicate exactly what had been produced at Columbus, what came off the line at New Lexington likely differed in some details. Mounting quality control issues during 1966–67 likely added further inconsistencies to the output.

The 1968 plant shutdown took 4–6 weeks to resolve. The length of this shutdown suggests that significant re-tooling of the production line likely occurred. Milpar’s acquisition by Whittaker Corp. brought both fresh thinking and competent engineering/manufacturing expertise to address the plant’s production line issues. In 1968, Whittaker Corp. also replaced Milpar’s New Lexington plant supervisors.[86] Under Whittaker Corp., plant staffing increased significantly, further suggesting that a significant “build-out” of the production line likely occurred. Given these circumstances, product coming off the resumed production line certainly differed from previous New Lexington production (and likely also from earlier Columbus production).

As detailed above, the massive backlog that had accrued by early 1968 was such that a disproportionate amount of bayonet production occurred in the final ten months of operation when Whittaker Corp. ran the plant. This would have magnified the incidence of any manufacturing changes introduced during the 1968 shutdown.

Blade Stamping Method

As reported in Cunningham, Milpar developed a unique patented process to manufacture blades. Patent 3,218,892, filed April 30, 1962, regarding a Metal Working Process that used cold stamping to form carbon steel blades. [87]The patent was filed jointly by Jerome Nakrin and Eugene Fresch; and assigned to Milpar.[88] The benefit of this unconventional stamping method was to eliminate the surface grinding otherwise required to shape the blade. Based on examination of cold-stamped Milpar blades, only the edge was applied by grinding.

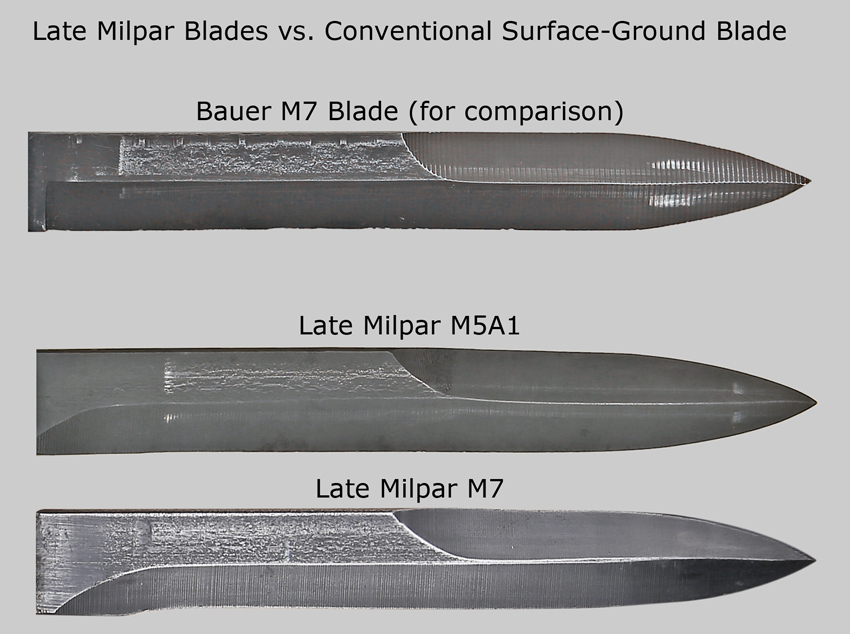

Cold-stamped Milpar blades have a distinct “hammered” appearance, where the lines that make up the blade’s profile typically appear dull. Cold-stamped blades also have a more tapered point. Figure 5 illustrates the different appearance of cold-stamped Milpar blades and a surface-ground blade.

Figure 5: Comparison image showing Milpar cold-stamped blades taken from sealed factory packaging vs. a Bauer M7 surface-ground blade.

Cold-stamped blades have a chamfer on each side of the spine. The chamfer’s appearance can vary from very crisp, to less-distinct, to almost rounded. Production line practices, wear on the stamping dies, and machine operator competency may be contributing factors to the variations. Figure 6 illustrates the variable appearance of Milpar cold-stamped blade spines.

Figure 6: Comparison image showing how Milpar cold-stamped blade spines can vary in appearance.

The example above taken from sealed packaging with a December 1961 packing date clearly exhibits the characteristics of the cold-stamping process. At this point, only 32,500 Milpar bayonets had been delivered, indicating that Milpar likely used this process from the outset of their bayonet production.

As discussed above, 1968 brought the most significant changes to Milpar’s production operations, so is the most likely point at which the blade stamping process changed. Whittaker Corp’s. need to satisfy government inspectors exasperated with Milpar’s backlogs and problematic output, would have introduced processes that they knew worked; not try appreciate Milpar’s one-off approach. Increased staffing in 1968 is also consistent with introduction of a more conventional blade production method.

Late-production Milpar blades appear surface-ground, more like those of other contractors. The lines making up the blade’s profile are sharp and the point more radiused. Vertical striations from surface-grinding are visible to varying degrees, depending on how aggressively the grinding was done. (Felix Mirando of Imperial Knife Co. indicated that with their bayonets, “we put it in the grinding machine and grind it down to a cutting edge in one pass through the machine.”[89]) The Milpar blade spine is also rounded and the runout sloped. These characteristics are observed together, suggesting that they were implemented concurrently, as would have been the case with a broad overhaul of the production process. Figure 7 illustrates two late Milpar blades alongside a Bauer M7 blade.

Figure 7: Image showing Milpar conventional surface-ground Milpar blades and Bauer M7 surface-ground blade.

In 1968, government specifications still called for the 90-degree runout. Government inspectors would have been appreciative of Whittaker’s intervention and inclined to work with Whittaker engineers in order to finally eliminate the quality issues and get the plant back in production. This probably explains the Government’s apparent willingness to accept a non-standard blade runout. While we do not have documentation of a variance allowing Milpar to use a sloped blade runout, precedent existed for government acceptance of a curved runout when a previous manufacturer (J & D Tool Co.) experienced challenges producing acceptable blades.[90]

In 1966–67, M7 bayonet deliveries would have been a top priority due to the need to equip U.S. forces with the M16 rifle. This prioritization is reflected in the observations of fewer Milpar M7 bayonets exhibiting the later, surface-ground blade characteristics; while M5A1 and M6 bayonets exhibiting these characteristics are more frequently encountered.

Blade Edge

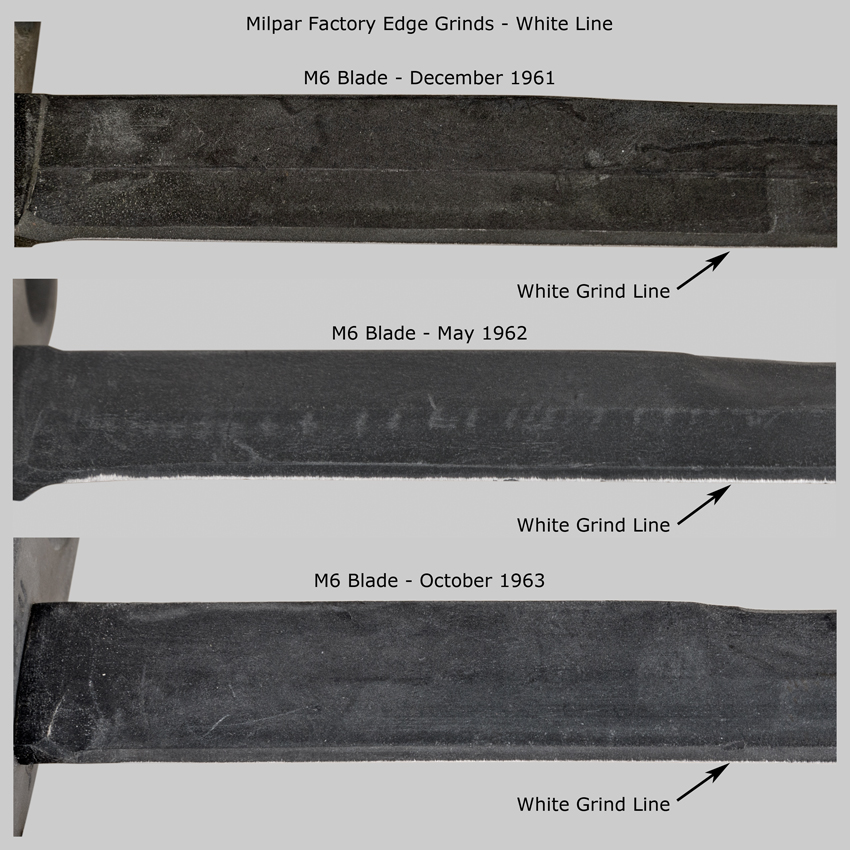

Milpar’s cold-stamped blade edge was a two-step, with a steep, coarsely-ground edge that was finished off with a very fine, almost invisible second edge. New 1961–63 production examples do have the “white line,” however, it is so thin as to be almost invisible unless turned to the light. It likely tarnished or wore away in service, giving collectors the impression that Milpar blades left the factory with no white line. However, Milpar’s two-step grinding process produced an edge that was not very sharp and required significantly more stoning to sharpen than blades from other contractors.[91] Figure 8 illustrates three Milpar M6 bayonets taken from sealed packaging, all of which exhibit a white line in their factory blade edge.

Figure 8: Image of Milpar M6 bayonets taken from sealed packaging dated in 1961, 1962 and 1963 showing the thin white line blade edge.

Research has shown that there were likely several episodes of commercial assembly using Milpar parts after completion of Milpar’s government contracts.

As detailed above, a quantity of bayonets was commercially-assembled by Whittaker Corp. in early 1970 and sold to a surplus dealer along with the remaining factory parts inventory. These bayonets may be indistinguishable from government production. They were assembled from government-contract parts, by former Milpar employees, on the existing Milpar production line. Gary Cunningham reported that the Milpar factory inventory was sold to a surplus dealer, whom he reliably-believed to have been Century Arms.[92] While Century may have assembled some bayonets on their own, much of the commercial-assembly attributed to Century could actually be the factory-assembled bayonets acquired in the sale.

Pennsylvania surplus dealer, William J. “Bill” Ricca, indicated that:

“When I starting going to the OGCA show in Columbus in 1974, there were loads of rejected blades, grips, and other parts that were produced at Milpar. The area was flooded. A large SGN dealer I know had lots of those parts also. The market was loaded with bayonets made up out of these rejected parts. There were even M5A1 Milpars with solid grips (no cut aways for the locking plungers), made into knives and sold much cheaper to those who either did not know it would not fit a rifle, or didn't care. In the Columbus Ohio area alone, there were thousand and thousand of those parts available. So logic says there were lots of bayonets produced with rejected parts and sold on this market, both M5A1 and M6.”[93]

Ricca’s contentions about rejected parts are consistent with the evidence detailed above. It is clear that Milpar experienced unusually-high rejections post-1966 and the New Lexington plant’s small footprint likely required disposal of rejected parts well before the 1970 inventory sale.

Stark non-conformities, such as: knives made from bayonet parts, bayonets with welded guards, etc. are obviously commercially-assembled. However, the prevalence of commercial assembly by surplus dealers needs to be considered in light of the approximately 1.9 million M5A1, M6, and M7 bayonets that Milpar made under government contracts.

While there will always be room for reasonable skepticism and scrutiny of Milpar bayonets on a case-by-case basis, it is important not to paint with too broad of a brush. In some cases, such as the Whittaker Corp./Milpar commercial bayonets, they are probably indistinguishable from government-contract examples, even to experts. Should we continue to worry about these? Probably not.

Defense Acceptance Stamp (DAS)

Milpar M6 bayonets are found both with and without the Defense Acceptance Stamp (DAS). Examples removed from sealed packaging show that the DAS was present from the outset of M6 production and was still in use in May 1962. Use of the DAS at Milpar appears to have been discontinued prior to October 1963. No Milpar M5A1 bayonet has been observed or reported marked with the DAS.

Evidence shows that the DAS was neither mandatory nor intended to signify that an item was accepted by the government. Sometimes, the DAS stamped into bayonets was lightly struck so could be faint, could wear away, or become obliterated during maintenance or refinishing. For these reasons, the presence or absence of a DAS should not be criteria for determining whether a bayonet is U.S. Government Issue (USGI).

More information on the DAS can be found in my working paper, Defense Acceptance Stamp Use on Bayonets and Scabbards.

Foreign Distributions and 1960s Bayonet Procurement

Foreign distributions do not appear to have been a premeditated factor driving bayonet procurements during the 1960s. Only one 1965–1975 bayonet contract is documented as being placed for foreign military sales (ref. contract DA-11-199-AMC-642, above). During the 1960s, the majority of M5A1 bayonet foreign distributions appear reactive to world events, most significantly: developments in Korea, the Vietnam War, and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.[94]

Procurement of M5A1 bayonets appears to lag foreign distributions, indicating that the majority of 1960s foreign distributions came from existing government stocks. For example: a procurement for 190,000 M5A1 bayonets occurred in 1962 (ref. Bayonet Contracts, above). From 1964–66, 267,351 M5A1 bayonets were reported distributed to foreign users.[95] The next large M5A1 bayonet procurement was awarded in June 1966 (ref. Bayonet Contracts, DA-11-199-AMC-726, above).

Evidence also shows that procurement of M5A1 bayonets during the 1960s was consistent with national defense needs. In early-1967, some of the active-duty Army and all of the National Guard were still equipped with the M1 rifle.[96] A national mobilization would have required issuing M5A1 bayonets to newly-raised U.S. forces. Under these circumstances, government stocks reduced by foreign distributions would have required prompt replenishment.

M6 bayonet production was completed during the 1960s, long prior to the vast majority of foreign M14 rifle distributions.[97] Only 26,102 M6 bayonets were reported distributed to foreign users from 1966–73, a quantity insufficient to influence procurement in any way.[98]

In 1966, when large M7 bayonet contracts were awarded to both Milpar and Conetta[99], DOD had a moratorium on providing M16 rifles to foreign users, as they were urgently needed to equip U.S. forces.[100]

Military Assistance Program (MAP) records show that the vast majority of grants made required that bayonets supplied from U.S. stocks be replaced through subsequent procurement.[101] While in some cases one might argue that replacement was not necessary (e.g., Bren-Dan M4 bayonets), it was government policy that replacements be procured, so they were.

Conclusion

Milpar has been a boon for fledgling American bayonet collectors. Almost every collection of even a handful includes a Milpar bayonet. This paper enables a better appreciation of the firm that produced these bayonets and a better understanding of Milpar’s bayonet production. Milpar’s experience was unique in many ways that affected its government-contract bayonet production.

The shadow cast by post-Milpar commercial assembly of bayonets is something that we have to live with as best we can. While concerns about commercial assembly should not be dismissed, they should not be overblown. Neither use of the DAS nor foreign distributions is relevant to explaining Milpar’s manufacturing variations.

Additional research is still needed, especially to document Milpar’s M7 bayonet contracts and shed further light on Milpar’s production methods.

[1] Polk’s Columbus City Directory, Vol. LXIX (Columbus, OH: R. L. Polk & Co., 1947), 1581, Ancestry.com.

[2] Polk’s, Vol. LXXI (1949), 189, Ancestry.com.

[3] “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” digital image s.v. "Frank M Rodgers," Ancestry.com.

[4] Henry L. Hunker, “Columbus, Ohio: The Industrial Evolution of a Commercial Center” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, 1953), 95, 100, 114, http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1486473800770369.

[5] In re Estate of Markiewicz, 71 Ohio Law Abs. 143 (1955), https://cite.case.law/ohio-law-abs/71/143/

[7] “Eugene Fresch is Graduate of OSU”, The Sandusky Register, Jun 12, 1952, 2, Newspapers.com.

[8] Polk’s, Vol. LXXIV (1953), 422, Ancestry.com.

[9] Polk’s, Vol. LXXV (1954), 419.

[10] “Ohio Family of Four Wiped Out as Plane Crashes on Wabash Farm”, The Indianapolis Star, Nov 29, 1954, 1, 11, Newspapers.com.

[12] Polk’s Vol. LXXVII (1956), 237, Ancestry.com.

[13] The Cleveland Directory Co’s. Parma (Cuyahoga County Ohio) City Directory, Vol. IX, (Cleveland, OH, The Cleveland Directory Company, 1958), 318, s.v. "Nakron, Jerome" Ancestry.com.

[14] “Inspectors,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, Nov 24, 1966, 37, Newspapers.com.

[15] Nakrin was listed in the 1958 Lakewood, OH, City Directory as Purchasing Agent, Standard Products Co.; in the 1959 Parma, OH, City Directory as VP Sales & Purchasing, Columbus Milpar Manufacturing Co.

[16] “Ohio, U.S., Death Records, 1908-1932, 1938-2018,” s.v. "Frank M Rodgers" (d. 5 Aug. 1960), Ancestry.com.

[17] “Del Palmer”, The Bradenton Herald, Jul 4, 2000, Local 2, Newspapers.com.

[18] Dun & Bradstreet Business Directory, s.v. “Allied Custom Molded Products, Inc,” accessed February 14, 2022, https://www.dnb.com/business-directory/company-profiles.allied_custom_molded_products_inc.1b928ed7786559f0bdee66b4b54bd329.html

[20] “Fremont Area Deaths, Louis J. Michles”, The News-Messenger, Feb 24, 1966, 2, Newspapers.com.

[21] “Fremont Area Deaths, Louis J. Michles”, The News-Messenger, Feb 24, 1966, 2, Newspapers.com.

[22] “Contract Should Boost Perry Employment”, The Newark Advocate, Mar 10, 1966, 22, Newspapers.com.

[23] “Milpar Co. to Diversify, Business Up”, The Newark Advocate, Aug 5, 1967, 19, Newspapers.com.

[24] NARA/AAD, Records of Prime Contracts Awarded by the Military Services and Agencies, created, 7/1/1965–6/30/1975, accessed January 30, 2022, http://aad.archives.gov/aad/series-description.jsp?s=492&cat=SB297&bc=sb,sl

[25] “Whittaker Adds Texas Company,” Daily News-Post, Mar 6, 1968, 5, Newspapers.com.

[26] Statistical Report on Mergers and Acquisitions, Report No. 6-15-18 (Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission, October 1973), 94, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/X5Sk6UJ0bIAC?hl=en&gbpv=1

[27] “Corporations: Whittaker says it has agreed to acquire Milpar”, The Los Angeles Times, Jan 30, 1968, III-7, Newspapers.com.

[28] “Council Renews Company’s Lease”

[29] “New Contract Won’t Help Perry Plant”, The Newark Advocate, Oct 7, 1968, 14, Newspapers.com.

[30] Thomas J. Murray, “Whittaker: Too Far Too Fast?” Dun’s, February 1970, 28 and 31.

[31] “Mil-Par’s Co’s. Plans Remain Uncertain”, The Newark Advocate, Dec 6, 1969, 8, Newspapers.com.

[32] “Mil-Par’s Future in Doubt”, The Newark Advocate, Apr 30, 1970, 10, Newspapers.com.

[33] Murray, “Whittaker: Too Far Too Fast?”

[34] Dun’s Staff, “The Ten Best-Managed Companies,” Dun’s, December 1970, 24.

[35] Federal Supply Classification Part 1, Groups and Classes, Cataloging Handbook H 2-1, (Defense Logistics Agency, Defense Logistics Services Center, 1986), 41, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Federal_Supply_Classification/0nEC-n_nHdYC?hl=en&gbpv=1

[36] “Three Plants of Columbus Milpar Co. Become Casualties of Vietnam War and Will Close: Closing of East Fulton St, East 5th Ave, and Cassady Operations Will Affect 350 Employees,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, Jan 16, 1970, A1. Posted by Gary Cunningham (bayonetman), US M5A1 bayonet, U.S. Militaria Forum, Nov 18, 2014, Us m5a1 bayonet - EDGED WEAPONS - U.S. Militaria Forum (usmilitariaforum.com)

[37] “Mil-Par’s Future in Doubt”

[38] “New Lex Gets New Industry; Plant to Assemble Land Mines”, The Logan Daily News, Mar 15, 1963, 2, Newspapers.com.

[39] “New Lexington, Perry County, Ohio, 1916”. 1916, https://oaks.kent.edu/sanborn/new-lexington-perry-county-ohio-1916

“New Lexington, Perry County, Ohio, 1950”. 1950. https://oaks.kent.edu/sanborn/new-lexington-perry-county-ohio-1950.

[40] Mil-Par to Keep Facility in New Lex”

[41] “New Lex Building May Be Idle”, The Newark Advocate, Mar 6, 1968, 15, Newspapers.com.

[42] Area Labor Market Trends, January 1963, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, 1963), 28, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/gdxYAAAAYAAJ?gbpv=1

[43] “DOD Pursues Active Program to Assist Small Business and Labor Surplus Areas,” Defense Industry Bulletin, Vol. 1 No. 8, (Washington DC, Department of Defense, August 1965), 22, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Defense_Industry_Bulletin/fmNHAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[44] The first contract found that was documented to the Westerville plant was awarded in November 1965.

[45] “Mil-Par to Keep Facility in New Lex”

[46] I found newspaper coverage of this job from October 1959 to May 1960.

[47] “District Briefs”, The Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum, Mar 7, 1960, 10, Newspapers.com.

“Firemen Called”, Mansfield News-Journal, Mar 5, 1960, 2, Newspapers.com.

[48] “Firefighters Make Five Runs in Galion Area”, The Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum, Nov 2, 1959, 10, Newspapers.com.

[49] It was common back then for newspapers to report who was treated in local hospitals and for what. Three different newspapers reported on injuries/accidents that occurred at the Milpar job site, so the situation there was well known.

[50] “106 Felled by Fumes at Firm in Columbus”, East Liverpool Review, Jan 25, 1962, 14, Newspapers.com.

[51] “New Lex Gets New Industry; Plant to Assemble Land Mines”

[52] “Council Renews Company’s Lease”

[53] “New Lex Council Hears Air Pollution Complaints”, The Newark Advocate, Sep 14, 1967, 22, Newspapers.com.

[54] “Mil-Par to Keep Facility in New Lex”

[55] “Say Detonators Were Stolen by 2 Children”, The Logan Daily News, Aug 4, 1969, 8, Newspapers.com.

[56] “Area Men Arrested in $20,000 Theft,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, Feb 11, 1970, 1, Newspapers.com.

[57] “Mil-Par to Keep Facility in New Lex”

[58] Officials Mum on New Lex Plant Plan”, The Newark Advocate, Apr 8, 1970, 16, Newspapers.com.

[59] “Mil-Par’s Future in Doubt”

[60] Bid Protest Decision, B-148124, (Washington, DC: Government Accounting Office, Apr. 13, 1962), accessed December 30, 2021, https://www.gao.gov/products/b-148124-0

[61] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards (Pennsylvania: Scott Duff Publications, 2015), 116.

[62] 1963 Annual Report to the President and Congress, (Washington, DC: Small Business Administration, 1964), 66, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/YRIEfuSL3tAC?gbpv=1

[63] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards, 120.

[64] Gary Cunningham, Bayonet Points 2014 (CD) (Parkersburg, WV: privately published, 2014), M7 Bayonets, 17.

[65] NARA/AAD, Records of Prime Contracts ...

[66] “Perry County Industries Production Up”, The Newark Advocate, Nov 12, 1965, 20, Newspapers.com.

[67] NARA AAD, Records of Prime Contracts ...

[68] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards, 120.

[70] “New Lex Gets New Industry; Plant to Assemble Land Mines”

[71] “Milpar Co. to Diversify, Business Up”

[72] “Contract Should Boost Perry Employment”.

[74] “Mil-Par’s Employment to Increase”, The Newark Advocate, Jan 19, 1967, 2, Newspapers.com.

[75] “Milpar Co. to Diversify, Business Up”

[76] “Mil-Par’s Co’s. Plans Remain Uncertain”

[77] “New Lex’s Milpar Plant Back in Production”, The Newark Advocate, Feb 21, 1968, 5, Newspapers.com.

[78] “New Lex Building May Be Idle”

[79] “New Lex’s Milpar Plant Back in Production”,

[80] “New Products to Keep Plant in Perry County”, The Newark Advocate, Aug 13, 1968, 14, Newspapers.com.

[81] NARA AAD, Records of Prime Contracts ...

[82] “Plant Not Likely to Reopen Soon in New Lexington”, The Newark Advocate, Jul 9, 1969, 5, Newspapers.com.

[83] “No Orders Closes Plant in New Lex”, The Newark Advocate, Mar 12, 1969, 8, Newspapers.com.

[84] Mil-Par Waits Government Order, The Newark Advocate, Jan 8, 1969, 14, Newspapers.com.

[85] “No Orders Closes Plant in New Lex”,

[86] “New Products to Keep Plant in Perry County”

[87] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards, 120.

[88] Eugene C. Fresch and Jerome Nakrin, Metal Working Process, Patent 3,218,892, filed Apr 30, 1962, and issued Nov 23, 1965, https://patents.google.com/patent/US3218892A

[89] Blackie Collins, The Pocketknife Manual—Building, Repairing and Refinishing Pocketknives, (Benchmark Division, Jenkins Metal Corporation, 1976), Interview with Felix Mirando.

[90] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards, 108.

[91] Lee Emerson, M14 Rifle History and Development, (privately published, 2009), 428, https://miamirifle-pistol.org/wp-content/uploads/M14-RHAD-Text-Only-Edition-00815.pdf

[92] Gary Cunningham, U.S. Knife Bayonets & Scabbards, 120.

[93] William J. “Bill” Ricca (Bill Ricca), “M6 Bayonets repros??? Commercial??” M14 Forum, December 5, 2009, https://www.m14forum.com/threads/m6-bayonets-repros-commercial.77337/

[94] NARA AAD, Records About Military Goods and Services Provided to Foreign Countries, created, ca. 10/1/1950 - 9/30/2004, accessed January 30, 2022, https://aad.archives.gov/aad/series-description.jsp?s=3284&cat=GS30&bc=,sl

[95] NARA AAD, Records About Military Goods and Services Provided to Foreign Countries ...

[96] Hearings on Military Posture and HR 9240, a Bill to Authorize Appropriations During Fiscal Year 1968 for Procurement ..., 90th Cong. 1326–27 (1967) (testimony of Gen. Harold Johnson, Army Chief of Staff), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hearings_on_Military_Posture_and_a_Bill/qj4uAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv1

[97] Lee Emerson, M14 Rifle History and Development, Text Only Version, (Las Vegas, NV: Privately Published, 2010), 124-28.

[99] Conetta’s M7 1966–67 M7 contracts amounted to $1.3 million, indicating that Conetta’s 1960s M7 production was nearly equal to Milpar’s. However, this amount may be overstated, as Conetta ended up owing the government a substantial sum for progress payments on contracted-for items not delivered at time of their closure. In any case, the 310,000-figure cited in Cunningham’s book is too low, so must represent a partial report.

[100] Department of the Army, Vietnam Studies: The Development and Training of the South Vietnamese Army 1950- 1972, CMH Pub 90-10-1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1975), 101, https://history.army.mil/html/books/090/90-10/

[101] NARA AAD, Records About Military Goods and Services Provided to Foreign Countries ...

© Ralph E. Cobb 2022 All Rights Reserved